Edward Yardeni introduced the world to a unique group of protestors in the early 1980s…

These protesters don’t hit the streets. They don’t file lawsuits. And they don’t crowdsource to raise money for their causes.

All they do is sell bonds.

Bond prices and yields have an inverse relationship. So as the conservative economist pointed out four decades ago, these protestors’ actions drive interest rates up.

You see, the Federal Reserve wants to set rates at one level. But if these so-called “bond vigilantes” are unhappy, their selling can overwhelm the central bank’s wishes.

Bond vigilantes were big in the early 1980s. And they came roaring back last week.

As I’ll explain today, the return of these vigilantes sent the bond market into a tizzy.

But notably, this group of protestors consists of individual traders who act on their own. They don’t make statements or issue press releases.

So we need to interpret everything on our own. And the standard interpretation is wrong…

Last Wednesday, Yardeni noted in the Financial Times that the bond vigilantes are angry about budget deficits. His view is common in investing circles.

But the data doesn’t support that conclusion…

In short, the bond vigilantes reared their heads a day before Yardeni’s write-up.

Sure, interest rates have risen a lot during this cycle. But the Fed has controlled it.

What happened last Tuesday (October 3) was a vigilante move…

For example, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Fund (TLT) plunged 2.2% that day.

Stocks rise and fall by 2.2% (or more) all the time. But bond-focused exchange-traded funds like TLT are a lot less volatile…

Since its July 2002 inception, TLT has been available for around 5,300 trading days. It has only fallen more than 2% in a day 96 times. That’s less than 2% of the time.

In other words, October 3 was a rare extreme. It was the work of the bond vigilantes.

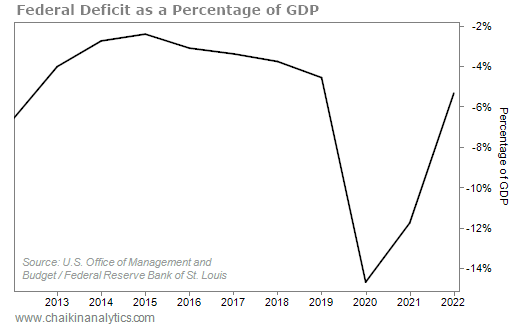

We analyze deficits and debt in a similar fashion. We can’t draw conclusions unless we view them in scale…

It’s one thing if I lend $100,000 to my neighbor to build a small restaurant. It’s a completely different thing if I lend $100,000 to a fast-food giant like McDonald’s (MCD).

So we evaluate deficits as a percentage of gross domestic product. Here’s the data over the past decade…

Obviously, the deficit wasn’t suddenly a new problem on October 3. It was (and still is) in the process of recovering from the pandemic-induced 2020 extreme.

But something else happened on October 3…

That day marked the unprecedented removal of Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy. He was voted out of office for working with rivals to keep the government open. And upon his removal, there was no clear plan for what to do next.

This historic move reminded me of something that happened in the early 1990s…

At the time, I covered a Brazil-focused closed-end fund as Fernando Collor de Mello became the country’s president.

The big issue in Brazil at that time was hyperinflation. (The year before that, prices rose nearly 1,973%.)

The Brazil-focused fund’s portfolio manager made an interesting observation about the country’s business and investment communities. He noted that they didn’t care whether Brazil implemented Plan A, Plan B, Plan C, or anything else.

Rather, they just craved stability and predictability.

The portfolio manager reasoned that these folks just wanted to know the ground rules in the first place. And they wanted confidence that the rules wouldn’t constantly get overhauled.

I suspect that’s the case with the bond vigilantes in the U.S. today. They want clear and stable ground rules.

But on October 3, Washington spit in their faces. Removing McCarthy without any clear plan of what would come next is the exact opposite of stability and predictability.

Now, look at this situation through the eyes of a lender…

Remember, the U.S. wants to borrow money for the next 20 to 30 years.

So let’s suppose your neighbor proposes to repay you for the $100,000 loan in 20 to 30 years. That’s a heck of a long time. A lot can (and will) happen over that period.

Wouldn’t you also place a higher premium on your ability to trust your neighbor’s emotional stability for such a long time?

So in the end, I don’t think today’s bond vigilantes are targeting deficits.

Instead, I believe they’re more worried about borrowers acting like petulant children. They want to lend to responsible adults.

And they’re telling Washington to grow up.

Good investing,

Marc Gerstein